Bakerloo Line extension - can London "stand on its own two feet"?

After hopes of government funding were dashed, the GLA Budget and Performance committee are exploring alternative methods for funding the long-awaited Bakerloo line extension through to Lewisham and on to Hayes.

The London Assembly Budget and Performance Committee meeting of 22 July centred around capital improvements for Transport for London (Tfl) and how to fund them.

The last government spending review was a disappointment for those hoping to see progress on the Bakerloo Line Extension and other transport projects, as it allocated no money to major infrastructure projects across London.

Committee chair Neil Garratt asked the panel of assembled experts: “What are the options that aren’t just asking government for money?”

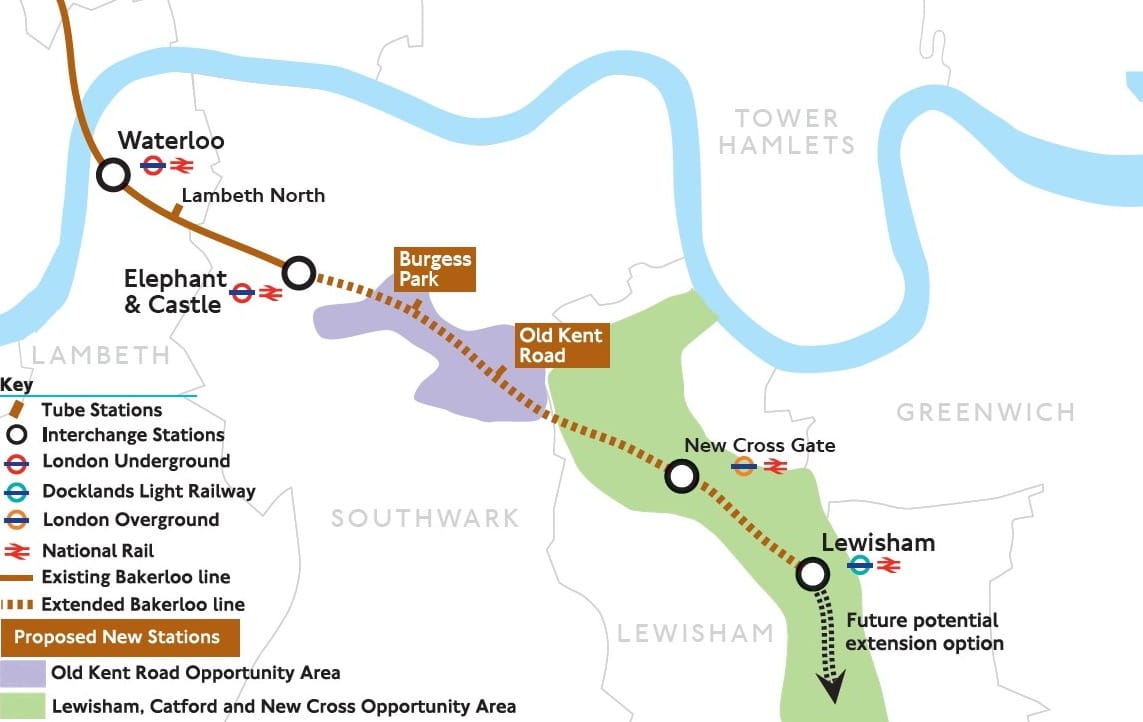

The proposed extension would take the Bakerloo line from its current terminus at Elephant and Castle to two new stations along Old Kent Road, with stops added to New Cross Gate and Lewisham. A second phase could include stops at Ladywell, Catford Bridge and more, all the way to Hayes.

The Back the Bakerloo campaign, organised by Southwark and Lewisham councils and others, argues that the extension will support over 100,000 new homes in London, and take over 20,000 cars off the road. According to the survey they commissioned, 89% of businesses and 76% of residents in the area support the proposals.

Phase 1 of the route was safeguarded in 2021 which means that new developments would not restrict building the line at a later date. The potential benefits have been much discussed.

Garratt noted that there are always trade offs and "no free lunches”.

Manish Gupta, Tfl corporate finance director, described three different methods for financing new projects.

“The first is that we fund them on a balance sheet .. the second method is that we can borrow money via public-private partnerships.” He provided Silvertown tunnel as an example.

“And the third method .. was used for the Northern Line extension, where a lot of money actually was obtained from land value capture. Crossrail was funded on a very similar basis.”

The Treasury’s “lack of imagination”

Professor Tony Travers is director of policy-focused urban research group LSE London. “London pays substantially more in total in tax than is spent in London," he said. "And so London is capable of generating tax revenue, with investment."

"But the difficulty is that we live in the most centralised country - England within the UK, in terms of public finance - in the world. So nothing can happen unless the Treasury sanctions it. And it’s not just a matter of the Treasury funding it ..

In London, what we need is access to mechanisms that allow developments to go ahead, and the Treasury at the moment is slightly lacking in imagination, it can’t bring itself to say, 'well, if London isn’t going to get money for these new schemes, why on Earth can’t it be given a more off the shelf, bespoke opportunity, to access tax increment finance deals, or PPPs, or whatever .. in a way that allows it to access its own potentially rising land values, in order to capture the uplift, in order to help fund its own projects and generate fare income?'

"But at the moment, London’s neither going to get the money from central government for these projects, nor, far as I can see, access to schemes that would allow itself to fund them. And that is a lack of imagination.”

With central government grants essentially out of the equation for funding infrastructure projects, the committee discussed recent high-profile projects which used different methods.

Silvertown Tunnel was built using a public-private partnership, and the Northern Line Extension used land value capture.

Public-Private Partnership

In a public-private partnership (PPP), an agreement is arranged between the government and the private sector, in which the private sector provides funds up front and is then paid back with interest over a long period.

Private financing initiatives (PFI) are not without controversy, with risks including high interest rates.

Vivek Kotecha when at the Centre for Health and the Public Interest, summarised the issues: “These guaranteed payments provide PFI companies and their lenders with substantial returns in the form of profit and interest which are in excess of returns on projects with similar risks.

They also lock public authorities into contracts for 25-30 years for cleaning and facilities maintenance services and sometimes require that they make payments for buildings which are no longer needed.”

The Silvertown tunnel was financed via the Riverlinx consortium, which also managed the construction and will operate and maintain it for the next 25 years. Tolls of £10 for HGVs and £4 for cars and small vans (at peak times) are being used to pay back investors over 25 years.

There was intense and widespread opposition to the project on the grounds that it would bring heavy traffic, noise and air pollution into some of the most deprived boroughs in London, and undermine climate targets.

However, the meeting hailed the PPP funding of the Silvertown tunnel as a success.

Land value capture

Tfl explains land value capture as “a set of mechanisms used to monetise the increase in land values that arise in the catchment area of public infrastructure projects.”

Essentially, if you build big infrastructure projects, the land around them increases in value, and capturing that change in value could fund the projects. Tfl theorise that this could be implemented in three different ways:

- A framework for assigning zonal value growth in Stamp Duty Land Tax

- Regular revaluations and full zonal retention of revaluation growth from business rates

- Creating a new land value capture charge – such as a transport premium charge.

The business rate is based on the open market rental value of a property. Land value capture presumes that the rental value would go up if a business had improved transit connections and a larger customer base due to increased densification.

In the case of the Northern Line Extension to Battersea Power Station, TfL was able to borrow against the presumption of higher business rates that would occur when the project was complete.

What’s Next

The central question posed by Garratt to open the meeting was: “Is it possible for London to stand on its own two feet and not rely on government funding?”

The options explored by the meeting involved innovative levers, some of which would need Treasury approval. None are without risk. But London waits for no committee, and towers of flats have begun to appear at some sites along Old Kent Road and the future route.

The ‘Bakerloop’ bus begins this autumn as a stop-gap measure to service the projected increased population.

As Gupta said, “We have to look at every possible option, and see what would work best.”